In the current issue of the Journal of Sleep Research, scholars summarize the results of a study of racial differences in how anxieties about violence impact adolescents’ sleep. They report that:

. . . race‐related stressors exacerbate risk for poor sleep among African American adolescents who experience more community violence concerns. . . .

That is, Black youth are afraid and thus sleep poorly, whereas adolescents of other races, they also state, do not experience these fears and thus sleep better.

It is easy to understand why this would be the case, in our racist society, but harrowing to think of the millions of Black youth who suffer from the predictable and traumatic consequences of long-term sleep deprivation. For them, this means bodies unhealed, memories unprocessed, and emotions unsorted. And their privations point to a gigantic loss for our culture as a whole. Who knows what manuscripts might have been written, what problems solved, or what feats accomplished had they simply been able to sleep through the night?

There is no way to measure the human potential lost as a result of their hardships, but this is a political issue and, as such, it can be corrected through action. While reflecting upon this, I realized that taking sleep seriously might mark a big shift for the left and how it understands the revolutionary lifestyle.

Prior to World War II, leftists held contradictory views of sleep. The first line of The International—”arise ye workers from your slumbers”— affirms the familiar association of sleep with ignorance and victimization. But there were also radicals who celebrated sleep, mainly because it is the setting in which dreams occur. The Surrealists felt that dreams scrambled the dominant society’s falsehoods in an emancipatory way. Radicals influenced by psychoanalysis saw dreams as the “royal road to the unconscious,” to use Freud’s words, and all the critical insights that it can provide.

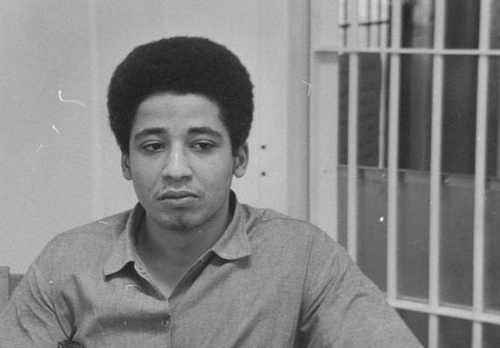

But leftist attitudes to sleep shifted in the 1960s, during the era of the “heroic guerrilla.” George Jackson’s collection of letters, Soledad Brother, offers a window into this. Jackson was a legendary figure in the Black Power movement, which was tied to and partially responsible for mobilizations among inmates in American prisons, where he spent most of his life. In addition to describing Jackson’s unique political world, his letters offer a meditation on tactics of self-fashioning that were urgently important to many at the time. How can a man who lives in a cage transform himself into a theorist and a writer and come to see himself as the author of his own destiny? Soledad Brother seemed to provide insight into this question, which is compelling for radicals and anyone concerned with the relationship between freedom and constraint. The book, which became a bestseller, came out shortly before Jackson was shot to death by a guard in the San Quentin State Prison.

How did Jackson remake himself? Engaging with others was a huge priority. The letters themselves demonstrate his investment in communicating with people on the outside and they contain many accounts of his ties with prisoners on the inside. And he followed a program of activities focused on self-transformation. He exercised for hours every day—he boasted that he could do 1000 pushups on his fingertips—and he enriched his mind with wide reading and disciplined study (he devoted an hour of each day to the study of speed-reading techniques and another to the dictionary). He also apparently smoked like a chimney—in one missive, he mentions that he had just finished his seventy-fifth cigarette of the day and it was still before breakfast.

But he was especially interested in sleep. He often commented on what he imagined his correspondents’ sleep practices to be; he challenged his father to produce evidence substantiating his views of sleep; and he frequently discussed his own sleep habits. We learn that he only slept for two or three hours nightly and felt guilty if he slept more. Though incarcerated, he saw himself as a man of action and appeared to shun sleep—hours devoted to it were hours not spent realizing revolutionary dreams. These dreams were well articulated and tangible for him. Though they may be deferred, as Langston Hughes’s famous poem noted, Jackson felt certain that they had occurred.

Jackson’s attitude toward sleep reflected the common wisdom of his time, but today we know that it is just as vital to our well-being as food and water. Forgoing it for sustained periods generates devastating physical, emotional, and psychological results, which is why sleep deprivation is a common torture at places like Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. And, as the report cited above indicates, we also know that compromised, inadequate sleep is another one of the injustices that white supremacy inflicts upon Black people.

For all the left’s focus on our working, waking hours, it is clear that contemporary radical movements must champion sleep, particularly Black sleep. And repairing the injuries caused by disrupted, insufficient rest suggests a different model of revolutionary action than that revealed in Soledad Brother. It will require not just guerilla wars and guerilla warriors, but also zones of disengagement, places that are quiet and dark, and militants who know how to create and enjoy settings that are unmistakably safe. These conditions must exist if sleep is to work its wonders for the long-burdened, long-terrorized Black youth as well as others.

~ Chuck Morse